During the first few months of 1923 a series of 16 articles written by Samuel Murdoch Crosbie, under the pen-name “Scouronian”, appeared in the pages of the ‘Kirkcudbrightshire Advertiser and Galloway News.’ Entitled “The Story of The Scaur; And the Water of Urr Shipping. ” it gives a fairly detailed look at the shipping of the north Solway in the days of the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Although set around the Scaur (now renamed Kippford) there is some Kirkcudbright interest. Accompanying images have been added for the webpage.

The Story of The Scaur; And the Water of Urr Shipping.

by Scouronian, 1923.

Page 1 of 2

Part 1.

Galloway’s great romancer, the late S.R. Crocket, has the following paragraph in one of his most delightful books, “Raiderland”:-

“To every Scot his own house, his own gate end, his own ingle nook is always the best, the most interesting, the only thing domestic worth singing and talking about.”

This meets my case so far as my native village is concerned. I have visited many villages in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, but never have I come across one that could satisfy my longings in every respect, as does the Scaur with its more modern name of Kippford. True it is a place of moods and tenses. When the Estuary of the Urr is in full tide, on whose banks the village stands, and the golden sun is shining on its waters the visitor may think it a perfect paradise. When the tide is out and the banks are laid bare, and the rain is pelting on them, even the most prejudiced amongst us feels that the outlook is somewhat dismal. But when you know the Scaur you cannot help admiring it. It is one of the cleanest and most picturesque of villages, and has such a look of prosperity about it, that situated as it is on the slope of the Muckle Hill with one tier of houses above another, one can only call it a miniature Torquay. Then the social life is so homely and distinctive, villagers and visitors vieing with each other in friendly intercourse, that the Scaur stands on a pedestal of it own compared with other seaside resorts. This is the reason, doubtless, why such large numbers of visitors return year after year, that the season, which only lasted two months of the year a little while ago, now extends from Easter right on to the end of October.

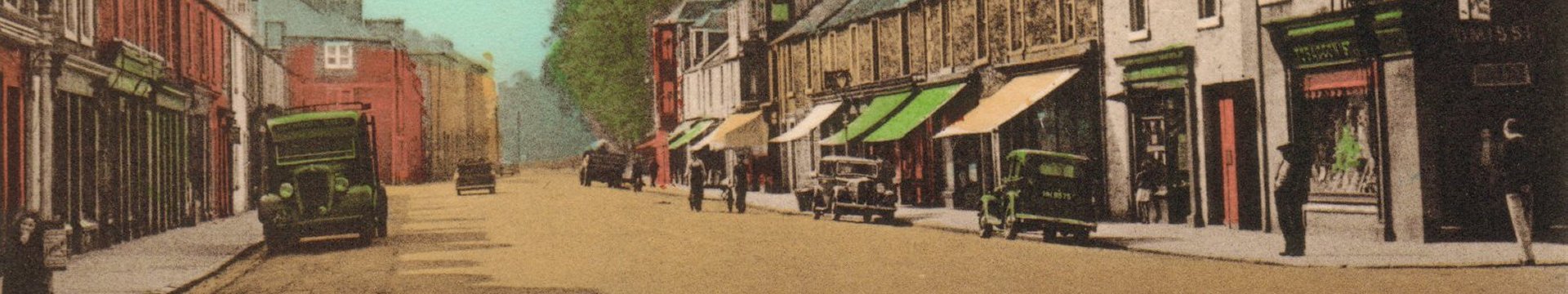

Sailing ship lying on the beach at Kippford

(The Stewartry Museum Collection)

Within living memory the Scaur has changed from an out of the world little hamlet of some eighteen cottages – most of them thatched – to a thriving busy village of more than double than number of dwellings, many of them well built and quite up-to-date. In those earlier days the Scaur was cut off from the outside world by the tide for a portion of each day as the only road into it was along the beach which was covered twice every twenty-four hours. There was no post-office, there were three public houses, there was no shop worthy of the name, and speaking generally the village was considered to be quite a century behind the times.

The making of the new road, thanks to the enterprise of two of the villagers, Messrs Donaldson and Clachrie, and the rebuilding of most of the old cottages, began to change all that. New houses were erected from time to time, the post-office was instituted, there is a shop where you are well served with most commodities, there are fine hotels, one public and two private, and there is excellent communication with Dalbeattie, the nearest town a little over four miles away. Motor cars and conveyances of every kind are to be seen in the village almost daily, and the vans of the Dalbeattie shopkeepers vie with each other in friendly rivalry in bringing the necessary supplies for the floating as well as the permanent population.

There are now two halls, the old one belonging to the Anchor Hotel capable of holding nearly 200 people, and the new erection of the British Legion that can accommodate at least 300. There are two tennis courts connected with the latter organisation, and there is also the ground requisite for a bowling green, which, if laid out would prove a boon to the neighbourhood. Despite the fact that the cost of building material still keeps high, the erection of new houses by private enterprise has already begun. Two fine dwellings of the bungalow type are approaching completion, and the plans of several others are being drawn up. The extension of the village may compel the County Council to introduce a system of water and sanitation that would bring the Scaur into line with all modern villages.

Until late years the story of the Scaur was bound up with its shipping industry, and therefore with the shipping of the Water of Urr. Sad to say, that industry and that shipping have almost entirely disappeared. True, there has been during the past year a slight recrudescence of the latter. Several schooners, and quite a number of steamers have passed up and down the river lately bringing cargoes from the Continent as well as from English ports, and the prospects for the future are certainly encouraging. But the trade can never be the same again. Never shall we see half-a-dozen schooners on the beach under repair, or awaiting their turn to go on the slip. The steamers go up the river one day and down the next, no waiting at the pawls near the Scaur for a fair wind as in the days of the old sloops and schooner.

A much respected, but all too infrequent contributor to the “K.A.”- who signs himself “Old Schoolboy,” has suggested that I should write the story of some of the old vessels and their skippers – names very familiar to every reader of this paper in days gone by – and I am attempting the task though with some trepidation. I tried many times to persuade the late Mr. Alex. Wilson, ship-owner and merchant, of Dalbeattie, to undertake the duty, but he always fought shy, and now silent in the tomb he lies who knew more about the sailors and the shipping of the river than any other living man.

Part 2.

Some time ago the R.C. Rymer propounded a query in his weekly column as follows, and one would like to provide the answer:-

“The ‘Thamas Green,’ the ‘John James,’

The famous ‘Good Intent,’

Ha’e vanished frae the Water,

And we wonder where they went.The ‘Jessie Maxwell’ is nae mair,

The auld ‘Witch o’ the Wave,’

Wi’ the guid auld ‘Importer,’

May have found a watery grave.”

Certainly it would be a pity were the story left untold, and so with the help of others who may supplement the information given in these columns, I have been able to recall old memories, and leave on record a tribute to those who carried on our coasting trade before it was killed by other means of transport.

And a feeling of pride rises in one’s mind at the very mention of the Water of Urr fleet. It made its influence felt on the commerce of the wide, wide world, for the young sailors whose training was begun on its staunchly built, well formed vessels oft-times went far afield and became famous on the ocean-going clippers of former days – the old Wind-jammers as on the steam “grey-hounds” of later times. The Water-of-Urr sailors have been renowned for their fearlessness as well as for their skill as navigators. Their praises have been sung and their exploits narrated wherever our language is spoken. The thrilling story of Captain Wilson of the “Emilie St. Pierre” will never be forgotten; it remains one of the epics of the sea. And this is only one of the many that might, and doubtless will, be told.

When reading the story of Christopher Columbus in our younger days we wondered at, and could not but admire, his temerity in daring to cross the Atlantic Ocean – sailing away into the then unknown West in that small vessel the “Pinta.” Yet it was no uncommon thing for our Water-of-Urr sailors to cross that same Western Ocean in vessels like the good old “North Star” that lay so long on the Merse near the Scaur – the admiration of artists, and the wonderment of visitors, and whose cindered remains now lie a shapeless mass. In those days this fine schooner of 150 tons – once a lightship in the River Mersey – had her state cabin for master and mates, and her forecastle for the ten seamen though very little larger than the coasting schooners of the present day, most of which are worked by crews less than half than number.

Shipowners then could well afford to provide larger crews as freights were much higher than they have been since the development of steam power. What experiences these sailors must have had, tempest tossed in the wild Atlantic in a mere cockle shell! And how they suffered from scurvy through living so long on salt junk especially when detained down the channel by the prevalence of east winds for weeks at a time! How they must have relished the scones and oatcakes of their homes after living so long on hard tack as their biscuits were called. The very mention of salt junk must have been nauseating to the poor sailors of these days. No wonder they were suspicious of it and had a special grace for it called the “Deep Water Sailors’ Grace.” The following copy of it was kindly supplied to me by Captain James Cumming:

Old horse, old horse, what brings you here?

You’ve carted stones for many a year.

At last knocked down with sore abuse,

You’re salted down for sailors’ use.

Sailors they do me despise,

They cut me up and damn my eyes,

Tear off the meat and leave my bones,

Then heave the rest to Davy Jones.

Little wonder that with such small slow-sailing craft long voyages were the rule rather than the exception. Little wonder that scurvy was such a common complaint in those days. Little wonder that so many of these little vessels sailed away and were never heard of more. Whenever I hear of such sad losses, and there have been very many such as will be shown later on, the words of the poet Malcolm, learned in Barnbarroch School, come into my mind:

“Oh! Were her tale of sorrow known

‘Twere something to the broken heart,

The pangs of doubt would then be gone

And fancy’s endless dream depart!

It may not be; there is no ray

By which her doom we may explore,

We only know – she sailed away

And ne’er was seen or heard of more.”

The responsibility of the skippers of these sailing vessels must have been pretty heavy. They had not only to navigate, but to manage everything connected with the vessel and its cargo, and they had to render a faithful account to the owners when they reached the home port. I have before me the account book or log of the sloop “Druid,” sailed by Captain Donaldson in the years 1825 to 1834. It is chiefly a record of the disbursements and freights during these years but it makes most interesting reading. On the disbursement side we see that the ship carpenters were paid 3/- a day, that a gallon of whisky at 6/- was provided for the sea stock every few weeks, that coal was sold for 1/- a bushel, that wool was 5d a stone, cheese 5d a pound, tea 6/- a pound, sugar 6d a pound, and that lime was bought at 10½d a bushel and sold at 1/4. One cannot but admire the care and exactitude with which the accounts were kept, even to the halfpenny when hundreds of pounds were in question.

In writing about the Water of Urr shipping the fact must not be overlooked that at one time and another there have been shipbuilding yards in different parts of the river. The Scaur has always been the chief centre of this industry. Palnackie, formerly known as Garden, took second place for some years, thanks to the enterprise of the late Mr. Samuel Wilson of Orchardton, whose fame as a mariner and shipowner will be referred to in due course. It will be new to many, however, that vessels were also built at Dalbeattie port, at Shannon Creek, and at Rockcliffe.

The shipbuilding at the Scaur may be divided into two periods – the earlier and the later. In the early days of last century, the keels of vessels were laid on the beach at the end of the houses where Mrs. Cumming now carries on the one and only shop in the village, but the vessels were mostly of the smaller size. Mr. James Brown was one of the first to begin shipbuilding at the Scaur and he was closely followed by Messrs. Henry, James and John Cumming, who carried it on most successfully for several generations.

How two of the brothers Cumming left the Scaur when boys and walked along the Colvend coast, gradually making their way round into Cumberland until they reached Whitehaven, where they served their apprenticeship as carpenters and shipbuilders, and how they returned to the Scaur to carry out their trade is one of those stories that thrill young hearts, and tend to show how almost insuperable difficulties may be overcome, and were overcome in the days of our fathers and grandfathers. Surely an object lesson and an example of patience and perseverance to the rising generation, too many of whom are being petted and spoiled, much to the detriment of stamina and character.

Part 3

In later times, that is about the year 1860, there was a revival of the shipbuilding industry that had been in abeyance for some years chiefly through the boom in the repairing part of the business. It was no unusual thing to see three or four vessels awaiting their turn on the Scaur beach for repairs, and the carpenters could not therefore be spared for new work. However, in the year abovementioned, Mr. James Cumming laid the keep of a vessel in a new shipbuilding yard about the centre of the village – the site of my father and mother’s garden until we left the Scaur for Liverpool in 1859 – and set the men to work on her when opportunity offered. Slowly and surely the solid walls of a stately ship rose before our eyes, and after some seven years of patience and perseverance, she was launched into her natural element under the inspiring and inspiriting name of the “Try Again.” This fine vessel after sailing the seven seas from 1867 to 1906 was lost with all hands through a collision in the Bristol Channel.

A second venture followed in the building and launching of the “Balcary Lass,” another splendid specimen of the shipbuilder’s art. Some time afterwards she left Labrador for the British Isles, and was never heard of more, one of those mysterious disappearances that must have broken the heart of many a sailor’s wife.

When a boy I was at the launching of the first vessel at Palnackie, and I think I see her being christened the “Almorness” as she began to move down the slippery ways that enabled her to leap into the arms of the sea in the presence of a great crowd of spectators. She foundered in a squall off the Goodwin Sands and all hands were lost.

One vessel built at Dalbeattie Port, though christened the “Jane Elizabeth,” was known by the nickname “God’s Curse,” because of this ejaculation being made by the skipper when the lady who was naming her failed to break the whisky bottle against her bow. More will be said about the “Jane Elizabeth” further on.

There must have been two attempts to found shipbuilding yards at the Shannon Creek. I have been informed that a vessel called the “Queen of Naples” was built here to the order of Mr. Crosbie of Kipp, but that was before my time. In later years Mr. Thompson made preparations to revive the industry. The walls of the saw-pit may yet be seen near the Ashiebank Quarry Pier. For some reason or other nothing further was done and the idea was ultimately abandoned.

From time immemorial the Scaur carpenters were treated to an allowance of whisky twice a day. Their hours were long; they worked from 6 o’clock in the morning till 6 in the evening for about 3/- a day with half-an-hour for breakfast and an hour for dinner. And they did work! There was no ca’ canny about them! It was a pleasure to watch them caulking the sides of a vessel. I think I hear, even yet, the music of their rhythmical blows on the caulking irons as the oak beam was being driven into the seams between the planks. But every morning at 11, and every afternoon at 3, the sounds would cease and the men would march away to the “Anchor” or one of the other public houses for their dram. And just as regularly preparation was made for the reception of these hard sons of toil by the proprietor of the Inn who covered every chair-bottom with newspaper to save them from the tar on the clothes of the workmen. The whisky was 2d a glass in those days – not the 1s 4d as in post-war times! But even then, this custom added considerably to the repair account of every vessel overhauled.

Even my younger readers will remember the slipway on the Scaur beach. Prior to its introduction, the vessels in need of serious repairs were moored broadside as far up the beach as possible at high tide and raised as far as possible by means of screws, a very slow and cumbrous method. The launch from this position required great preparation. On one occasion, and one only, did a mishap take place. Everything was ready, the logs well greased, one at the bow and another at the stern. The order was given to knock away the last wedges so that the vessel – it was the “Suffolk Hero” – might glide into the water. One of the carpenters bungled his part of the work, failing to knock away the wedges at his end. The other end of the vessel thus began to move and the consequence was that she fell on the beach, the launch proving a failure. Luckily the schooner was not much damaged but she had to be raised on the blocks once more by means of the screws, and her cradle renewed, before being sent into her watery home.

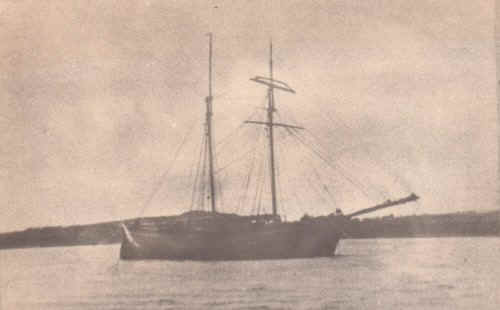

Sailing vessel crossing the road on the slipway

(The Stewartry Museum Collection)

The use of the slipway simplified matters. The vessel was floated onto a cradle that was hauled up the rails laid on the beach by means of a chain attached to a capstan in the building yard, then firmly secured by blocks, and shores, that is, long stout beams laid against the side of the vessel. The launches from this position were great events and brought together a large concourse of spectators on every occasion. I was near the bow of that great warship, the “Audacious,” when she was launched from Cammel-Laird’s yard at Birkenhead but it did not thrill me as I was thrilled at the Scaur as I stood watching Mr. Cumming knock out the pin that released the cradle and sent the vessel on her journey into the water. It may be remembered that the “Audacious” was sunk by the Germans early in the war on the north coast of Ireland. The matter was kept a secret until the American press gave the show away. Even then there were contradictions that mystified the public.

The slipway was sold or otherwise disposed of about ten years ago. Prior to that time the old saw-pit had been filled up, but nearly the whole of the front of the village was part of the beach with here large heaps of small boulders that had been brought as ballast by various vessels from time to time. The removal of the slipway enabled the Improvement Committee of the village to continue the road as far as the shop, use the boulders to build a sea wall, and level up the front so as to form two greens on which have been provided garden seats for visitors. The expense connected with all this was defrayed by funds raised by concerts and a few voluntary contributions from visitors.

Part 4

Since the decay of the shipbuilding industry at the Scaur, endeavours have been made to attract visitors. The provision of seats in the village, and round the hillside paths have helped in this direction. Through the kindly interest of Mr. L. M. Dinwiddie, one of the governors of the Hutton Trust, these paths have been greatly improved, rough places have been made plain, brackens are cut annually, stiles and gates have been renewed, and the road to Rough Firth kept in reasonable repair. This latter road was made by the residents themselves at a very slight cost, most of the work being done by volunteers. Only those who remember the communication between the Scaur and Rough Firth before this road was made can have any idea what a boon it has been. It is a pleasure to walk down to the bathing place nowadays, instead of a difficult matter as formerly.

For those who prefer walking to golfing or tennis or boating, the attractions of the Scaur and neighbourhood are very varied and altogether delightful. The Jubilee Path that leads round the Muckle Hill is bad to beat and is a constant delight to visitors. It leads you to Knockyknowe, one of the favourite resorts for youths and maidens gay to loll in the sun and gaze of Silver Solway and the coast of Cumberland. It also leads you to Rockcliffe and the Solway Cliffs at Castle Point, where is one of the finest sandy bays of the coast, near which is the famous mill-stone quarry, and not far from which are Gitcher’s Isle and the “Elbe” memorial.

Perhaps the most favourite walk, and certainly the most frequently enthused about, is the walk round the Velvet Path behind the Mark Hill. Another walk that equals if not excels the last named, but is not so accessible, is that to Almorness Cottage, better known as Cockle Ha’en. To do this one properly, and with greater comfort, the visitor must cross to the Glen Brow steps by boat an hour before high water, returning a couple of hours later on the ebbing tide. The view from the old fort on the knowe behind the cottage enables one to get a glimpse of both valleys, Orchardton Tower, the Urr Estuary, and the Solway Firth, a magnificent panorama.

An excellent view of the four lochs of Co’en; Duff’s, Clonyard, White and Barean, locally known as Ironnash Loch, can be obtained from the top of Doon Hill, which can be reached by skirting the Kipp Wood opposite Orchard Knowes loaning, or by going round the road and up past Auchenhill Farm. On a clear day Silloth and the Isle of Man may also be seen from the summit, whilst the Urr valley stands out in all its loveliness from North Glen to Dalbeattie. There is no obstruction to the view now that the wood has been cut down.

A few hours on Rough Isle or Heston, the Rathan of The Raiders, are worth much from a health point of view. Both of these islands are favourite picnicking points.

Many visitors want to know if there is any fishing near the Scaur. Permission is needed to fish in Duff’s Loch, the only one where trout is to be found. In the other lochs pike and perch may be fished. Sea fishing by line is seldom attempted, simply because it is hardly ever attended with success unless the lines are laid on the banks and visited between the tides. Visitors occasionally enjoy a day’s trawling with the Annan fishermen.

The industries of the Scaur only require a very few words. There are two or three trawlers or fishing boats belonging to the village but during the last year or two very little has been done. The cost of transport by rail is still too high to make it a paying job. A considerable quantity of mussels is dispatched almost daily to the English markets. This indeed is the only live industry at the present time. A few years ago the gathering of cockles on the Rough Firth banks gave occupation to a few people, but since the channel altered its course, that trade has entirely ceased. It may interest the younger generation to know that a few years ago the channel went close round Glen Isle point, across to Starvation Point, and kept quite near to the rocks along Gibb’s Hole, as far as Horse Isles Bay, known locally as Whitesand Bay. Now it takes a straight course towards the middle of Gibb’s Hole.

For many years a regatta was held annually at the Scaur. It was instituted when there were very few boats in the place except those belonging to the vessels that happened to be in the river at the time. As years rolled on, boats of all classes were built and entered in the competitions for the various silver cups and valuable money prizes that had been provided by visitors and friends. It became one of the principle events of the kind in the South of Scotland and attracted hundreds of spectators year after year. It was discontinued during the Great War and has not been revived.

Two years ago, however, a number of enthusiastic yachtsmen banded themselves together and formed the Solway Sailing Club. They looked about them and secured a new design of dinghy, 14 feet in length, and broad of beam with centre board. Six of these have already been built by Messrs Sayers, Kirkcudbright, and during the last summer races were run fortnightly. Increasing interest has been taken in these club competitions, and most likely the enthusiasm engendered may lead to the revival of the annual regatta in the near future.

A word or two about the facilities for bathing may not be out of place. The most popular, and therefore the most frequented bathing place, is at Rough Firth. There are two bays and both are well patronised. When the tide is out at the Scaur many of the visitors walk to Castle Point where there is a beautiful sandy bay, Glen Isle Bay and Whiteport are also favourite resorts of bathers but boats are required for conyeyance to these two places.

One of the greatest improvements ever effected in the Scaur was the laying down of the jetty. It is useful the whole year through, but in the season it is the constant centre of attraction inasmuch as it enables all and sundry to embark or disembark with comfort at all times of the tide when boating or yachting. Fishing smacks too come to the jetty with their harvest of the sea, and on their arrival there is a rush of buyers from the village, making quite a busy scene.

The granite pier is sometimes used by the fishing boats, but as the woodwork is fast decaying great care has to be taken in walking along that part of it. The attempt to resuscitate the granite quarries seems to have been unsuccessful so far.

Part 5.

And now let me try to answer the query of our friend R.C Rymer. The “Thomas Green,” a wee schooner of some 30 tons, was sunk at Heston after plying between Cumberland and the Water of Urr for many years, and often sailed by her owner, Captain Wilson.

The “John and James” was a fine schooner of 115 tons, and under the command of Captain John Tait was long successfully engaged in trading to all parts of the coast. She was wrecked on the pier at Whitehaven whilst running for shelter from a severe gale that caught her on her voyage from Liverpool to the Water of Urr. Luckily all hands were saved, and her skipper, though now advanced in years and fast approaching the four score, still seems as brisk as ever. Along with Mr. William Clachrie he provides for the wants of the visitors at the Scaur, amongst whom he is very popular, by taking them into the Solway or up the river in their fine motor boat, the “Doreen,” formerly belonging to Mr. W. Theodore Carr, of Carlisle.

In the “John and James” Captain Tait was often as far north as Shetland, picking up fish for Leith and Greenock. At other times he would bring kelp from Shetland to Glasgow, returning north with cargoes of salt. Formerly the kelp industry proved a gold mine round the island of Lewis, and Lord Leverhulme has been trying to develop the industry afresh. After the wreck of the “John and James,” Captain Tait sailed the “North Barrule” for nine years, but retired from the sea on the death of his wife fourteen years ago.

The “Good Intent” was sold into Silloth, where she was converted into a dredger with such good purpose that when the dock was cleared of mud, the dock gates were burst open. Captain George Wilson was her skipper for some time.

The “Witch o’ the Wave” was sold into Ireland where at Portaferry as her headquarters she is still going as strong as ever with the help of a motor engine.

The “Importer” was wrecked in Brighouse Bay, where she was discharging a load of coals. A gale springing up drove her from her anchorage, but the crew managed to reach the shore. Her namesake, the “New Importer,” was lost with all hands on a voyage from Liverpool to the Water of Urr in 1891. The bodies of the crew were cast up several months afterwards on different parts of the coast. The loss of this vessel with so many valuable lives inspired the writer of these lines to agitate more strongly for the establishment of a lighthouse on the island of Heston. Thanks chiefly to Major Maxwell of Kirkennan, who took the matter up, a lighthouse was erected the following year.

The “Jessie Maxwell” lay long on the Scaur beach – a sheer hulk – all that was left of her after taking fire at sea laden with lime. Gradually she was broken up and used for firewood, but I still have in my possession her sternboard with her name painted thereon. I think I see her creeping up the river on the incoming tide in her dilapidated condition. Captain Bryson was her skipper for many years.

Having cleared the decks so far, let us now bring under notice the representatives of that long line of skippers who have adorned the pages of history connected with the winding Urr. And first I must mention Captain Thomas Candlish, that splendid specimen of the ancient mariner type, who left the sea some years ago to live at Rockcliffe, where he still takes a lively interest in the yachts there, though well over 90 years of age. Hale and hearty he has ever been, and always the same, bright-eyed, alert and intelligent as when I first knew him some 65 years ago. In those days he was captain of the schooner “Lucy End,” of which he was part owner at first and then owner. We boys were always pleased to see the Captain’s vessel on the Scaur beach, for then we were sure to get a cabin biscuit, and the use of the boat to row about the river. There were no pleasure boats at that time on the Scaur. Even after reaching manhood’s years I have sat in his cabin in a Liverpool dock munching a biscuit and listening to his wonderful stories of smuggling connected with Palnackie, many of which I have re-told in the columns of the “K.A.” as the years rolled on. An ancestor of Captain Candlish was, I understand, the prototype of Lucky M’Candlish, one of the characters in Sir Walter Scott’s “Guy Mannering.”

The gallant Captain was born in Palnackie, and began the sea as a boy in the sloop “Henrietta,” his father being the skipper. At the age of 18 he was appointed skipper of the sloop “Jessie,” built at the Scaur, and was said to be a “forbye fortunate young fellow” in getting command of a vessel at that early age. After selling the “Lucy End” mentioned above he bought the “Eagle,” one of the Montrose and London clippers, and sailed her two or three year. Then he sold her and bought the “Rover,” a large schooner, and her he swapped for another vessel and a sum of money. Afterwards he sailed the “Mantura” for many years, and in her made numerous voyages to the west of Ireland and the north of Scotland.

To his credit be it said, Captain Candlish never lost a vessel – a remarkable record in such a long life, especially when one considers the dangers connected with the navigation of the Solway and other parts of our rock-bound coasts, It may be noted that the schooner “Margaret and Mary,” belonging to the Captain, was lying inside Rough Isle laden with coals when a gale sprung up, caused her to drag her anchors, and threw her on the rocks at Rockcliffe, where she became a total wreck. Captain Candlish, however, was not on board at the time.

This fine old mariner had two sons, both of whom began their seafaring lives in vessels belonging to the Water of Urr. The elder, Captain John, became skipper of the “Mantura” when his father took command of the “Gelert,” but the greater part of his time at sea was spent in command of coasting steamers. Retiring a few years ago, he took up his residence in Dalbeattie, but he is an almost daily visitor to Rockcliffe, where, like his father, he takes a lively interest in the yachts, as well as everything connected with the local shipping. The younger son, Captain Charles, also went into the steam-coasting trade until the war broke out, when he offered his services to his King and country though much over the age, and was sent to France to take the command of barges carrying ammunition. There his health broke down, and the gastric trouble contracted was the cause of his death at sea a year or two later.

Captain John Candlish, a brother of Captain Thomas Candlish, died at Rockcliffe several years ago after many years’ life at sea as skipper of Water of Urr vessels engaged in the coasting trade. He was master of the “Thomas Graham” at one time – a vessel that was lost at sea on the night of the storm that caused the Tay Bridge disaster.

Part 6.

Another hale and hearty skipper fast approaching the veteran age is Captain Robert Edgar, one of our most respected villagers. He retired from the sea a year or two ago, but is aye ready to pilot a boat up the river, or do a hand’s turn for a friend. At the age of 14, Captain Edgar joined the “Wee Brig” under Capt. M’Lellan. After sailing with Capt. Samuel Ewart in the “Euphemia” and Captain Dixon Black in the “Eulalie,” names well known locally, he joined the “Sheitan” under Captain Samuel Murdoch, of Dalbeattie, of whom more anon. Then he was mate and skipper of the “Gallovidian,” for some time trading to Bristol, Ireland, and Fort William, after which he commanded the “Mochrum Lass” for 10 years, the “Maggie Kelso” for 15 years and the “Margaret Ann” for about 12 years, until the last-named was sold into Ireland during the war. His last command was the “General Havelock,” trading between Dumfries and Cumberland.

During the half century of his sea life Captain Edgar never lost a vessel, and thus, like Captain Thomas Candlish, he has proved himself a careful and skilful navigator. Two years before he retired, a big steamer just rubbed the end of the bowsprit of the “Margaret Ann.” So near a shave was it that the crew got into the boat thinking the end had come. The Captain, however, remained on board. May this fine old mariner long live to pilot vessels up and down the Water of Urr.! Six of the Captain’s sons became sailors, two being lost at sea, three are officers, and one an apprentice in the Mercantile Marine.

The “Margaret Ann”

The schooner “Ben Gullion” was a well-known trader connected with the Water of Urr and for many years she was commanded by Captain James Ewart, who hailed from Palnackie. For reasons of health Captain Ewart gave up the sea, and during the past few years he has been a successful farmer at Boreland of Colvend, and a highly respected elder of Colvend Church. It is interesting to note that the “Ben Gullion” has lately resumed her connection with the Water of Urr after a long absence in other parts of the coast.

Another well-known Colvend family has still representatives of the seafaring class in our midst. I refer to the sons of Captain Charles Bie, who owned the fine schooner “William Thompson,” and sailed her for many years. One of them, Captain John Bie, succeeded his father as skipper of the “William Thompson,” and then sailed the “Annie Heron” and the “Annie B. Smith” for some time, carrying coals chiefly to various places around the coast. He is now living in retirement in Rockcliffe, where he is as popular, with young people especially, as ever he was in his sea-going days. Captain William Bie, another son, is still ploughing the seas in the Mercantile Marine. The “Annie Heron,” a pretty model of a schooner, was sold into Wales much to the regret of many people in the Water of Urr. The “William Thompson” was broken up in Wexford.

One of our youngest skipper, who is keeping up the reputation of the Water of Urr sailors by his skill, energy and courtesy is Captain David Duke, whose home is at the Scaur. He began his sea-faring career in the “William Thompson” under Captain John Bie, mentioned in the proceeding paragraph. After a short service before the mast in the “Ben Gullion,” he was appointed mate of the “Resolution,” another local vessel then commanded by the late Captain John Murdoch. At the early age of 25 he was made skipper of the “Lady Helen,” and afterwards of the “Warsash,” on which vessel he traded for seven years between Liverpool and Dalbeattie. Then he took command of the “Dolphin,” since sold into the Orkneys, after the death of Captain William Sharp, who was killed by a falling block as the vessel was entering the river Mersey. In later times Captain Duke had charge of the “Annie B. Smith” until she was sold during the war, the “Ulverston” and the “Enigma.” Just now he commands, and partly owns, the “Adolf,” an iron schooner bought from the Germans, and is likely to do a good general trade round the coast when her motor engine is installed. The “Warsash” was burnt at the water’s edge in the Kingston Dock, Glasgow, when a warehouse took fire.

The “Enigma” deserves a paragraph all to herself. This old schooner is said to have been used as a slave ship at one time, and as a pirate ship at another. Whatever she has been, she was certainly a well-built, stout old craft, as I saw her on the Scaur beach a few months ago. She left Whitehaven at the beginning of December, and two or three days afterwards her wreckage was cast up on the Cumberland coast. It is surmised that she foundered in a gale that sprang up soon after she sailed, all hands being lost with her. Captain Pearson, of Kirkcudbright, was her skipper, having succeeded Captain Duke when she was sold out of the Water of Urr. Another tragedy of the sea!

For several generations the best-known schooner connected with the Water of Urr was, perhaps, the “Gallovidian,” belonging to the late Captain John Cumming, and sailed by him for a number of years until he was required at home to carry on the shipbuilding business when his brother, Mr. James Cumming, passed away, respected an revered by all. Many clever sailors from Galloway received their early training on the “Gallovidian.” When near the end of her long career, she lay on the Scaur beach until she was sold into Maryport, where she was accidentally burnt.

Two sons of Captain John Cumming became sailors. One of them, Captain Henry Cumming, was lost a sea during the war. He received his earlier training on the “Gallovidian,” but afterwards joined the Mercantile Marine. The other, Captain James Cumming, began his seafaring life in the “Gallovidian,” but like so many of our young sailors, left the coasting trade for deep-water navigation. After sailing the seven seas in windjammers and steamers, he left the sea in 1914, and since that time has made himself useful in many ways at the Scaur, especially in connection with his yacht and with those of the Solway Sailing Club, which he looks after with great assiduity. Occasionally he does a little fishing on his own account.

Part 7.

Of the retired sea captains belonging to the Water of Urr the well-known and distinguished names Captain Cassidy, Captains John, James and Henry Rae, Captain Dornan and Captain Black rise before my mind, but these were all deep-water sailors, and hardly come into the category of Water-of-Urr skippers through not being trained in vessels sailing from the river.

It goes without saying that the full story of the Water of Urr skippers and their vessels, whose names have been household words to every reader of the “K.A.” during the last 65 years, would fill several volumes. My purpose is to put on record a brief allusion to those who have lived and moved and had their being within my memory, which goes back that length of time. When a boy of nine I began to take an interest in things. And I may be forgiven if I say that I have known everyone whose names have appeared or will appear in this story – many of them being lifelong friends.

In my boyhood’s days at the Scaur Captain Samuel Wilson and his brother, Captain George Wilson, were well-known skippers and ship-owners. The former was born in 1807 at Carsethorn, and served his apprenticeship on the brig “Elizabeth,” trading chiefly to the west of Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland. The first Water of Urr vessel he commanded was the “Jean” belonging to Mr M’Knight of Barlochan, a vessel of 50 tons burthen. With this small craft he traded with the east coast of Scotland, thus showing the inherent pluck and grit of his nature. He soon became owner of the “Glasgow,” a schooner of about 100 tons. Captain Wilson must have done excellent work in this vessel, as with her he realised a competency. At this period freights were very good. It was no uncommon event to deliver coasting cargoes at 15s to 20s a ton, or quite as much as what vessels latterly delivered tonnage in Australia.

In the great gale of the 7th January 1839, the “Glasgow” was one of six vessels that left Sligo, and only she and another reached their destination. In 1840 Captain Wilson married Miss Lammie of Orchard Knowes and settled in Palnackie where, in addition to his business as ship-owner and ship-builder, he added that of timber and coal merchant.

Captain Wilson had several narrow escapes from meeting a watery grave, the most striking being his escape from the wreck of his schooner, the “Elbe,” on 7th December 1867. He was coming across from Maryport in her as a passenger, and the vessel was anchored in Balcary Bay until there was water over the bar. With the incoming tide there rose a heavy gale from the southwest, and she struck the ground heavily in floating. The cables snapped, sails were set, and the crew hoped to get her into the Water of Urr for safety. To their dismay they found that the rudder had gone in the bumping, and the vessel was unsteerable. Her boat also had broken adrift. Thus she was at the mercy of the waves, and all endeavour to guide her into the estuary of the river failing, she drifted towards Glenstocking cliffs. As she approached them, Captain Wilson gave the order “Every man for himself,” and when she struck several of the crew clambered on the rocks. The next wave again brought the vessel near the cliff, and two more jumped ashore safely. One remained on board, and those on the rocks noted his blanched face as the vessel was carried away from the cliffs. Luckily, however, another huge wave brought her back, and enabled the last of the seven to reach solid ground and safety. Then the “Elbe” sheared about and sailed away into the Solway, sinking like a stone about a mile from the shore before the eyes of the crew and some onlookers who had been drawn to the spot. A wonderful and providential deliverance indeed! A cairn of stones, erected by Captain Wilson and friends, stands near the place where the crew landed.

In his 94th year Captain Wilson underwent an operation in the Edinburgh Hospital, having his left hand amputated, the result of it being crushed some years previously. He lived some time after that, hale and hearty to the last, passing away at Orchardton within a couple of years of his 100th birthday, a true Water of Urr mariner.

His brother, Captain George Wilson, also lived to a good old age, having made his home in Dalbeattie, where he founded the well-known firm of coal and ship-merchants carried on in latter years by his son Mr. Alex. Wilson, who lately “crossed the bar,” deeply lamented by old and young. I have memories of Captain George Wilson coming down to the Scaur in his gig whenever any of his vessels happened to be on the beach. His seagoing days were over then, but he was ever the fine old son of the sea. The “Good Intent” was one of his favourite schooners – a very significant name.

In the nature of things some men figure more prominently in the public eye than others, and that without any desire on their part to do so. Such a one was Captain John M’Lellan, who begun his seagoing career as a boy on his father’s vessel, the “Elizabeth,” popularly known as the “Wee Brig,” already mentioned in this story, and who became one of the best-known captains of the Mercantile Marine. He was born at Barnbarroch in 1843, but was schooled at Palnackie, where his parents went to live in his early boyhood. After serving his apprenticeship on the “Wee Brig,” he joined the “Rover” under Captain Thomas Candlish, who still speaks in glowing terms of “one of the smartest seamen he ever come across.” But the coasting trade was not for Captain John M’Lellan. After a year in the “Rover” he went to Liverpool to enter the foreign trade. It is worthy of note that a brother of his took his place on the “Rover” and lost his life when the vessel was wrecked on the very next voyage. How true the old Scripture saying “One shall be taken and the other left.” A brother of Captain Edgar was also lost on the vessel.

At the age of 23, Captain John M’Lellan was made commander of the “Vanguard,” a large sailing ship, and he soon became one of the shining lights of the Mercantile Marine. For 20 years he voyaged the whole world over, never losing a vessel, and giving examples of pluck and resourcefulness, an instance of which may be given. On one occasion, when his ship caught fire, he carried a barrel of gunpowder out of the burning cabin and threw it overboard – a feat that doubtless saved the vessel from utter destruction, as well as the lives of all onboard.

In November 1886 Captain M’Lellan was invited to join the Liverpool Salvage Association, and thenceforward was opened up for him even a more brilliant chapter of his interesting and romantic career. By this Association he was sent to all quarters of the globe to survey wrecks and salvage them when at all possible. His most noteworthy successes in this connection were the salving of the “Knight Commander” and the “Seuvic,” for both of which he was honoured and rewarded by grateful underwriters. After his retirement Captain M’Lellan occasionally visited the Water of Urr. He died in 1914, and was laid to rest in Buittle Churchyard.