During the first few months of 1923 a series of 16 articles written by Samuel Murdoch Crosbie, under the pen-name “Scouronian”, appeared in the pages of the ‘Kirkcudbrightshire Advertiser and Galloway News.’ Entitled “The Story of The Scaur; And the Water of Urr Shipping. ” it gives a fairly detailed look at the shipping of the north Solway in the days of the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Although set around the Scaur (now renamed Kippford) there is some Kirkcudbright interest. Accompanying images have been added for the webpage.

The Story of The Scaur; And the Water of Urr Shipping.

by Scouronian, 1923.

Page 2 of 2

Part 8.

In the middle of the field adjoining Barcloy Mill, Colvend, and lying to the eastward of its loaning stood for many generations a small thatched cottage. It was demolished a few years ago, and only a flat patch of ground now marks the spot. In this homely, humble dwelling, a highly respected, hard-working, successful shoemaker – Mr Samuel Murdoch – lived with his wife for over half a century, and reared a family of seven sons and three daughters, one of whom was the mother of the writer of this story. Two of the sons followed the trade of their father, the other five all took to the sea, and so come into the story of the Water of Urr sailors.

The eldest son, Captain Ebenezer Murdoch, had a great reputation as a skipper in Water of Urr vessels. He also had a large family, two of whom, Captain Joseph Murdoch and Captain Thomas Murdoch, were well known and skilful commanders of ocean going ships.

The second son, Captain Andrew Murdoch, was skipper of the “Robert and Helen” until she was wrecked on the Mull of Kintyre in a dense fog. The crew escaped with their lives by climbing the precipitous cliffs of that rockbound coast. He then took command of a fine new vessel christened the “Brothers,” because he and two of his brothers purchased her. On a voyage up the west coast of Scotland he died very suddenly when at the wheel falling into the arms of his son John who was mate of the vessel. He was buried in Tobermory Churchyard. This son, John, succeeded his father as skipper of the “Brothers” and afterwards sailed first the “Isabelle” and then the “Resolution.” He was said to be one of the finest sailors that ever trod the decks. Three sons of Captain John Murdoch joined the sea. Of these Captain James Murdoch is skipper of the “Raymond,” and well maintains the reputation of our Water of Urr sailors.

Mr Samuel Murdoch’s third sailor son was Captain James Murdoch, who was skipper of the large sloop “Freedom” for many years, and carried on a successful trade around the coast. He received his earlier training under Captain George Wilson in the “Betsy.” On one rather stormy voyage when nearing the Cumberland coast, Captain James Murdoch was washed overboard, but a succeeding wave luckily washed him back on deck – one of those providential deliverances we have read about on very rare occasions. He died at the Scaur well over the four score, and his remains lie in Co’en Kirkyard. The “Freedom” was lost in Belfast Lough only a few years ago.

Captain James Murdoch had three sons, all of whom became commanders of ocean going ships after being trained in vessels belonging to the Water of Urr engaged in the coasting trade. The eldest, Captain Samuel Murdoch, father of Lieutenant William Murdoch of the ill-fated “Titanic,” served his apprenticeship with his father in the “Freedom,” but afterwards became commander of large ships like the well-known clipper “Knight Companion,” trading chiefly between Liverpool and San Francisco, in both of which ports his memory is still revered. He was perhaps one of the best known, most successful, and most highly respected master mariners hailing from the Water of Urr. After retiring from the sea, he lived in Dalbeattie, but frequently visited his native village the Scaur. The loss of his son William in the “Titanic” was a great blow to him – one from which he never recovered. He passed away not long afterwards and was buried in Dalbeattie Cemetery. Of Captain James Murdoch’s two other sons, Captain John died at sea, and Captain William perished in the “Mary,” along with Captain William Wilson when that vessel was wrecked near Rascarrel on her voyage from Cumberland to the Water of Urr.

Captain Thorburn, a son-in-law of Captain James Murdoch, lost his life in the “Dundonald” when that splendid four-master was wrecked on the Auckland Islands. The full story of that remarkable shipwreck – how Captain Thorburn and his son James, along with half the crew, were drowned soon after the vessel struck; how the survivors were discovered on one of the islands several months afterwards by the Government relief ship; how they subsisted during all that time – may be found in a book inspired by one of the mates of the vessel. But the story of the mental suffering endured by the near and dear ones of the Captain and his crew, the agony of hopes long deferred, and then blasted in some cases, will never be know.

A watery grave claimed the two remaining sons of my grandfather, Captain Alexander Murdoch being drowned in a Hull dock whilst boarding his ship, and Captain Charles Murdoch, the youngest of the seven being lost with all on board in the Atlantic on a voyage from Cuba in the West Indies to Great Britain. His vessel was never heard of and was supposed to have foundered in a heavy gale that was reported at the time. The sea has certainly demanded a heavy toll from the Murdoch family.

A distant relative of the family was Captain David Murdoch of the Scaur, who sailed the “Importer” for a number of years, trading chiefly between Liverpool and the Water of Urr. He was a general favourite, and his death at a comparatively early age was much regretted. The anxieties connected with sea life in the coasting trade undermined a constitution not too robust. And no wonder! When one thinks of the dangers to be guarded in these small vessels in running from one port to another, danger of collision, danger of sudden storms, irregular meals, it is astonishing that so many live to a good old age.

One of the smartest and trimmest schooners that ever sailed out of the Water of Urr to trade between Dalbeattie and Liverpool was the “Mary Agnes,” built at Barnstaple in 1882 and belonging to the Messrs Newall, Craignair Quarries. Many years did she carry on the good work under the command of Captain Thomas Hume, another of those faithful, clever mariners whose memory will long be cherished. The “Mary Agnes” was lost off the Mersey Bar with all hands, but prior to that Captain Hume had left her and she had been sold into the west of England.

The “Elizabeth” or “Wee Brig” has been mentioned several times in the course of this narrative. It may be interesting to note that this vessel was originally a French Corvette before being bought into the Water of Urr, and that she ended her days as a coal hulk at Sligo. Many fine sailors received their early training on this bonnie vessel.

I have also previously referred to the “Jane Elizabeth.” He skipper for some years was Captain Charles Clachrie, father of Mr. Robert Clachrie who died last year at the Scaur and who was one of the crew rescued from the “Elbe” when she was lost off Glenstocking. In that same gale the “Jane Elizabeth” was making for the Water of Urr and to save her from being dashed on the rocks, Captain Clachrie ran her on the sandy shore at Rockcliffe and scuttled her – the crew walking ashore when the tide receded. He has seen the peril of the “Elbe” and did not learn of his son’s safety until some time afterwards. When the gale moderated the “Jane Elizabeth” was repaired and resumed her voyage. These incidents were the talk of the countryside for many a long day. The “Jane Elizabeth” went ashore on the north coast of Ireland and became a total wreck.

Part 9

At this point it may be interesting to note that half a century ago there were at least three or four distinct types on vessels trading in the Water of Urr. There was the wherry, a small vessel engaged chiefly in bringing over coals from Cumberland. Then there was a sloop, a one-masted vessel of various tonnage. The larger traded all round the coast and carried a crew of three or four, including the skipper, whilst the smaller ones kept nearer home with a crew consisting of a skipper and someone to help him. The schooners are well known to the present generation as they still survive to remind us of the glories of the past as regards coasting craft. The brigs have entirely disappeared from the Water of Urr. They had two masts, and had yards, or square sails, on each mast. The three-masted ships and barques were only seen in Gibb’s Hole when discharging a load of timber from Quebec or some other foreign port. And oh! What a delight it was to hear the chanty singing of the sailors as they ran round the capstan, and to watch the great splash of water when the log was ejected from the “port-hole” in the bow. Although the vessels were lying a mile off, “Ranza, boys, Ranza,” as the sound was borne on the summer breeze, up to our little village. And then the joy of seeing the rafts of logs when they were drifted or towed up to the Scaur beach – but those are bygone days.

As my readers may have noticed, the number of families connected with the sea generation after generation was very large. The Bie’s, Candlishes, Cummings, Edgars and Murdochs have already been mentioned. Amongst the others, the Hallidays come into this category. Before my day Captain James Halliday lived at the Scaur, and commanded several vessels, including the “Jessie,” the “Thomas Nelson Black,” and the “Henrietta.” Our old friend, Captain Thomas Candlish of Selma, Rockcliffe, when a boy sailed under Captain Halliday who, in his earlier days, had some exciting experiences. On one occasion whilst serving his apprenticeship on a vessel commanded by a Scaur skipper, the Press Gang – that nightmare of early Victorian days – came on board in the Bristol Channel and took him off. Owing to the sturdy protestations of the skipper, however, he was liberated and thus escaped what might have been a long service on a man-o-war ship.

One of his sons, Captain William Halliday, began his career as an apprentice serving part of his time on a brig called the “Pilot” of Annan, belonging to Messrs Nicholson of that port, and commanded by Captain Thomas Murdoch of the Scaur, and the remainder of his time in the “Henry Brougham” under Captain M’Creadie who lived in Dalbeattie. On completing his apprenticeship he sailed on a vessel named the “Breeze” under the command of Captain William Murdoch, another Scaur skipper. On a voyage to Buenos Ayres Captain Murdoch died of Cholera shortly after crossing the equator and was buried at sea. Captain Halliday took command of the vessel though only 23 years of age, took her to her destination, and then brought her back to Falmouth. After this he was in command of several well-known barques before he ultimately went into steam. The Captain Murdochs referred to in this paragraph were relations of my grandfather, but belonged to another branch of the family and lived at the Scaur. Captain David Murdoch of the “Importer” belonged to this off-shoot of the clan.

The other son, Captain John Halliday, served his apprenticeship on a vessel called the “Mark” named after the hill behind the Scaur where she was built, and commanded by Captain J. Cumming of the Scaur. Afterwards he was chiefly engaged in the foreign trade. When he was chief mate of a barque called the “Tamuero” there were three John Hallidays on board. The Captain, the second mate and himself, all three hailing from Galloway but not related. They used nick-names to distinguish one from the other!

In my boyhood’s days there was no railway in the Stewartry, and Palnackie being the nearest port to Castle Douglas, was naturally the centre of a considerable shipping trade. That prettily situated village has turned out quite a number of distinguished sailors, some of whom have already been mentioned in this story. There were others who in their early days came all the way from Palnackie to Barnbarroch school and with whom we had a stern tussle on the school green, but they passed from my ken through my removal to Liverpool, and I must leave it to others to do justice to them. I have already referred to Captain James Ewart, a Palnackie skipper. His father, Captain Samuel Ewart, sailed the “Billow” for Messrs Black and M’Minn, carrying coals between Cumberland and Auchencairn. Afterwards he bought the “Euphemia” and sailed her for a number of years until he retired from the sea.

There are two Captain Blacks with whom I am acquainted. Captain George Black, who is now on the American side of the Atlantic, served his apprenticeship in the employ of Messrs Rae, Liverpool, and was not at any time in one of the Water of Urr vessels. The other, Captain Thomas Black, began his career in the “Snowdon Lass” with his father Captain John Black. In 1875 he sailed under Captain James Bell in the barquentine “Blue and White,” chiefly in the Newfoundland and Mediterranean trade. He was second mate of the “Fleetwing” and the “Atlas” engaged in the Australian and Indian trade. After being chief mate of the barquentine “Volador” he went into steam, joining the State Line, sailing between Glasgow and New York. He was captain of coasting steamers for 22 years, during which time he took the racing yacht “Caress” from Gourock to Boston Bay, along with Captain John Barr, well known as the skipper of the “Thistle” in the race for the America Cup. He was also for several years commander of two well known vessels, the “Solway Firth” and the “Pentland Firth.” Although now practically retired from the sea-faring life, Captain Black has not altogether given up his connection with Neptune’s domain, as he regularly takes part in the contests of the Solway Yacht Club with his trim little yacht, “Waterwitch.” Long may he continue to do so!

Time and again I have noticed with astonishment and admiration how readily these skippers transferred their command from one vessel to another when called upon to do so. At a moment’s notice they would literally take up their bed and walk on board with their belongings, give the order to hoist the sail, raise the anchor, and off they went on their voyage. In connection with Captain Black the “Snowdon Lass” is once more mentioned. At one time she was commanded by Captain John M’Knight, the father of my old school fellow at Barnbarroch school – Mr David McKnight – with whom I still delight to fight over again our old school battles. Captain M’Knight was also skipper of the “Good Intent” and the “Thammas Green,” names never to be forgotten in our river story.

Part 10.

Captain James Clachrie, a relative of the last named skipper, began his sea life in one of the Water of Urr vessels, the “Heart of Oak,” but afterwards went into the foreign trade. When he retired to his home at Rough Firth he took a very active interest in the Kippford regattas and, along with his brother Mr. William Clachrie, built boat after boat until he succeeded in carrying off the coveted prize – a silver cup – from his rival competitors, who sailed English built boats.

Captain John Campbell was another of our well-known Scaur skippers. For some time he sailed the “Mark,” one of the vessels built in the early days of the Scaur shipbuilding. This vessel was lost in the Solway Firth with all hands.

Of the vessels already mentioned the fate of the following may be noted:- The “Mochrum Lass” was sold into Dundee, and was taken to that port by way of the Forth and Clyde Canal by three Water of Urr sailors – Messrs A. Clark, J. Walker and R. Edgar.

The “Maggie Kelso” was sold into Ireland, and is still engaged in the coasting trade.

The “Liberty” long sailed by Captain Joe Clark, who afterwards became the ferryman at the Scaur, was allowed to rot her bones on Allonby beach.

The remains of the “Kitty” are yet to be found on the banks of the river near Palnackie.

Captain Edward Howell, at one time the ferryman, sailed his little vessel, the “Swift,” with his wife as mate, until she was wrecked in Rascarrel Bay. Old Ned, as he was called, was accidentally drowned one dark night when mooring his boat at the Scaur.

Captain John Sloan, of Dalbeattie, sailed the “John and Sarah” for some time. His son Captain Nathan Sloan, was skipper of the “Heart of Oak” and other local vessels, but afterwards went to take command of coasting steamers.

The “Heart of Oak” was last commanded by Captain James Clachrie, another Co’en man, now residing at Creetown. The old vessel was laid up in Wigtown, and fell to pieces near the harbour.

Then we must mention Captain Robert Clachrie and Captain John Aitken, both of whom became commanders of large ships engaged in the foreign trade, and were held in high repute as successful mariners. Captain Aitken’s end was rather tragical. His vessel, having sprung a leak, was foundering in the Atlantic, and the crew took to the boats, but the Captain refused to leave his ship and went down with her.

Many pages might be written of quaint sayings and stirring incidents connected with these old-time skippers, but one or two must suffice in this brief story. To illustrate the former, I may quote a portion of the prayer of old Captain C.R. who asked his maker to save him and his vessel from shipwreck, adding “I am not like one of those hypocritical bodies that trouble you all the time, and if you will only spare our lives this time it will be a lang time before I trouble you again.” Can you wonder that his prayer was answered?

Another old worthy told of the cleverness of his son in the following significant words – “Oor Jamie made an ash bucket oot o’ his head, and he has got enough wood left to make anither.”

A painting of one of the old Water of Urr sloops belonging to the late Mr. Alex. Wilson, and hanging for the last few years in his office, disclosed a quaint custom of the skippers of the days gone by. We have seen pictures of cricketers playing in tall silk hats, or “chimney pots” as they were nicknamed, but it will be news to many that the skippers of coasting vessels also indulged in this luxury. The picture disclosed the fact however. What kind of head-wear they used in a gale of wind is not known, unless it was a kind of night-cap such as I remember having once seen in my boyish days on the head of an old skipper.

The story of Captain Wilson and the “Emilie St. Pierre,” mentioned earlier on, is well known to the older ones amongst us, but it is worth telling again and again, for the sake of the younger generation. It was the time of the war Civil War in America, when the Northern States, called the Federals, were fighting to prevent the southern states, called the Confederates, from breaking away and becoming independent. The latter were the cotton growing States, and the supply of cotton to the Lancashire factories had been almost entirely stopped by the Federal warships blockading the Confederate ports. Captain Wilson, like many other British skippers managed to run the blockade – that is, break through the line of war vessels – and got away with his vessel, the “Emilie St. Pierre,” laden with a cargo of cotton. She was intercepted afterwards, however, by a Federal cruiser, all her crew taken prisoners except the cook, the steward, and Captain Wilson, who was left to help to navigate the vessel.

A lieutenant and seventeen men were sent on board with instructions to take the ship to New York. She never reached that port. Watching his opportunity, he determined to retake his vessel, and took the cook and steward into his confidence. First of all he secured the lieutenant in his cabin and gagged him. Then he ordered the seventeen men into the hold on some pretence or other, and whilst they were there he put on the hatches, thus imprisoning them. This done, he altered the vessel’s course and made for Liverpool, which port he reached after several days’ anxiety and privation on the part of himself and the two men who had so well supported him in his daring exploit. For salving his ship, and such a valuable cargo of cotton, Captain Wilson was rewarded and feted, both in Liverpool and Galloway, whilst the cook and steward also received presents of money. Captain Wilson was a native of Colvend, and therefore the Water of Urr can claim him as one of its brilliant sons.

Part 11.

As old age creeps on one seems inclined more to dwell upon the past and talk about it much to the boredom of young people. One even dares to speak about the “good old times” occasionally, although that well worn expression is very threadbare and less frequently used now-a-days, for the simple reason that we have made such advances in every branch of our lives, that the “good times” are to be found in the present day. Perhaps my young readers will bear with me whilst I draw upon the past and present at the Scaur for some illustrations of this point.

When the village consisted of thatched cottages for the most part, it sometimes happened that a roof was blown off, and the family had to find fresh quarters until it was repaired. When a small boy I remember being carried in a blanket to a neighbour’s house during a storm after such an accident. The children of the present day will not have their slumbers disturbed in this way.

Our home lessons were learned in the dim light of an ill-smelling glass-less naptha lamp, whose malodorous fumes haunt me even yet when I think about it, or by the light of a tallow candle that had been made by the mother of the house. In modern times the children have the benefit of paraffin lamps whose light in many ways is preferable to the gas or even the electricity of city homes.

On the moonless winter evenings when the stars were hid, we had to carry a lantern when going from one part of the village to another a short time ago, now there are three fine carbide lamps that illuminate the whole place.

As regards weather, that of the “good old times” would doubtless be preferred by the youth of the present generation, for in those days we could depend upon frost and snow for several weeks nearly every winter, when curling, skating, and sliding would be in full swing. The exercise occasioned by such sport was simply a more healthy kind than any that can be indulged in during the murky, mild winters of recent years.

Less than forty years ago an occasional high tide in winter would flood several of the houses in the village. Never shall I forget the sight that met my eyes as I passed along the village on my way to school one morning. Right up against the front of Magnet Cottage was a vessel, the “Margaret and Mary,” with her yard arm on the roof of the house. An exceedingly stormy high tide had torn her from her moorings and washed her into that position. A very remarkable thing about it was the revelation that the only one of the crew onboard knew nothing about it until daylight when the tide had receded. He had slept through it all. Since the new road was made and the sea wall built such an incident could not possibly take place, nor can any of the houses be flooded as in bygone days.

For some years the milk for the household had been brought to the door by one or other of the local farmers. In the “good old times,” we boys had to go direct from school to one of the farms and carry the big can of skimmed milk sometimes across the hills to our home. This was a task not always to our liking but it was lightened when several of us went on the same errand. And was there not milk for our porridge at the end of our journey as well as next morning for our breakfast? We youngsters were allowed very little tea and not much loaf bread. Homemade soda scones and oatmeal cakes were the better alternatives. These with a flask of milk consisted of our daily noon meal at school, whilst porridge and milk for our morning and evening meals completed our bill of fare. And who will say that hardy, sturdy frames were not built up on such plain food? It is not all to the good that “the halesome parritch, chief o’ Scotia’s food” has disappeared from so many homes in later times.

How well off we are with our modern means of transport! By the motor-bus or the bicycle we can be whisked from the Scaur to Dalbeattie in a few minutes, whereas in the “good old times” we had only the “cuddy” or the “cuddy cairt” to convey us, unless we took to “shank’s pony,” our usual means of locomotion. But what a useful “cuddy” it was, and what a smart clever body its owner was! The latter even ran to the toon for the doctor in her stocking feet in a case of urgency, and the writer of this story has reason to thank his stars on two occasions when this good-hearted soul undertook such an errand of mercy. Nor did she hesitate to cross the river and walk to Castle Douglas, a distance of six or seven miles Sabbath after Sabbath in order to worship her Maker in the church of her choice – the Cameronian Kirk in town. What think ye of that ye young people who consider it too great a distance to walk the two miles to Co’en Kirk? The memory of the Scaur mother is hallowed to some of us even yet. Since her day we have had for several decades a faithful general carrier in Mr. Robert Thomson, who took up the work of the late Mr. Robert McQueen. Year in, year out, in horse waggonettes or motor buses, he has conveyed us and our packages and looked after our interests generally in that respect. It is no easy job to please the public in such a business but his imperturbable nature and independent character have carried him through the troubles and trials of busman’s life with great success. As years roll on, and bodily girth increases, he finds himself less nimble than of yore, so whilst taking a general supervision still, he leaves the brunt of the work to his two faithful sons, James taking charge of motor buses, and John of the motor car. They are all ably assisted by Mrs Thomson who is everybody’s body, and who amidst all her other multifarious duties has acted as treasurer to the Village Improvement Committee for many years much to the satisfaction of everyone concerned.

During the last few years, a motor has been installed in connection with the Pines Golf Hotel and Mr. Douglas M’Kinlay attends to this part of the business. The next development in the matter of transport can only be the introduction of the aeroplane or air-ship! Unfortunately there is not a level field near the Scaur on which such machines could land with perfect safety, and so the village will be handicapped in this particular.

No story of the Scaur would be complete without a reference to the work carried on in connection with the Post Office. Only those in close contact with the place can form any idea of the amount of correspondence carried on by letters, wires and telephone, or the number of parcels received and sent away during the whole year but more especially during the summer months. The burden of the work falls necessarily on Miss Cumming, the postmistress, who has most capably filled that honourable and very responsible position for quite a number of years. Miss Cumming is a daughter of the Scaur, her father being a member of that firm of shipbuilders mentioned earlier in this story, who had so much to do with the making of the place. The other permanent officials are Miss Gibson, who has been an efficient and popular “postie” for some years, and her brother George, than whom there could not possibly be a more reliable or more speedy telegraph messenger.

Our closing words in this story must refer to the other public institution – the one and only shop which the Scaur possesses. For many years the business was carried on by the late Mr. James Donaldson, who was the first post-master of the village, and to whom along with Mr. William Clachrie, belongs the credit of getting the road made into the village. Then the late Miss Margaret M’Kinnel took up the business and provided for the wants of the populace until her health gave way, after which Miss Barbara M’Knight became the provider, and for some years her shop was one of the amenities of the place as well as a source of admiration to visitors, especially those hailing from across the Border. On her retirement a few years ago Mrs. James Cumming took over the business which has developed to a wonderful extent, and the shop more than ever is worthy of the title conferred on it of “universal provider.” Long may the good lady who looks after its destinies continue to greet her customers with the same cheeriness that has made her shop the popular resort it has become!

Part 12.

Half a century ago there was a Liverpool preacher whose nick-name was “Sixty-Minutes,” from the fact that his sermons were invariably spun out to that length of time much to the impatience of his younger hearers. After he had announced his “fourth and lastly,” there generally came the “In conclusion,” and sometimes “one word more” before he had finished. Something of the kind is taking place in this story. Last week’s instalment ended by saying that it was the closing words of the story.” Through the kindness of several friends who have supplied me with further information and who, like Oliver Twist, have asked for more, I must trespass on the patience of my readers by offering some additional instalments.

The reaches of the winding Urr are a puzzle to the crews of stranger vessels, and a continued source of anxiety even to those who are thoroughly acquainted with them. One old skipper naively remarked after a recent accident, “The devil himself would not know the channel in the ‘Deil’s Reach’ at the height of a spring tide.” Many interesting incidents might be quoted, but only one or two must suffice.

At the North Glen end of the reach is a big rock, known as the “Importer’s Stane.” It derives its name from the fact that the old schooner “Importer” was stranded on it in the distant past, and only salved as a result of much trouble and expense. The top portion of the stone was blasted away some time afterwards and the danger lessened, but even now it is a stumbling block and a rock of offence. The schooner “Adolf,” mentioned in a previous article, spent a day or two on it last year, and sustained considerable damage to her stern as well as having had a portion of her cargo jettisoned. It may here be incidentally mentioned that this vessel has cast off her German name since her motor was installed, and will henceforth be known as the “Solway Lass” – a much more suitable cognomen for a vessel now belonging to the Water of Urr.

Within the last decade a valuable vessel was wrecked at the Black Stane, where a small portion of her remains may still be seen. She was a fine Welsh schooner, the “Cordelia,” outward bound laden with granite setts. There was a strong fresh current in the river, and the pilot strongly advised a postponement of the voyage, but the skipper persisted, with the result that when the vessel reached that particular bend of the river about midday a strong current drove her on the stone. The crew remained onboard expecting to get her off on the following tide. When the midnight tide came however, the vessel did not rise with it. She had broken her back, and the crew had to scramble ashore, where they camped until daybreak. A portion of her cargo was salved , and now lies on the Scaur beach, where it is gradually deteriorating. After the vessel had been dismantled she was blown up, as she interfered with the navigation of the river.

One more incident may be given, and for it I am indebted to a relation now resident in Liverpool. Twenty two years ago the schooner “Jane,” laden with 30 tons of granite, was lying at the pier of the Ashiebank Quarries, near Orchard Knowes. A gale of unusual force sprang up from the sou’west, driving the tide abnormally high. The waves were tremendous, and caused the “Jane” to break away from her moorings. She drifted away up towards Major Threshie’s house, and grounded on one of his fields. Next day the gale had subsided, and although the tides were high, the vessel was over one hundred yards above high water mark. The men thereupon set to, unloaded the cargo, dug a channel deep enough and wide enough to allow the schooner to be towed back into the river, and then reloaded her with the 30 tons.

Even below high water mark on the banks of the river, it was no unusual thing for a vessel to be dug out in order to prevent her being neaped and kept aground for a week or a fortnight. And when the sailors know their vessels at certain times cannot get sufficient depth to take them up the river to the Dub o’ Hass – as Dalbeattie Port is called – one can see how their responsibilities are increased, and how difficult it is to understand the navigation of the river.

It would seem that the abnormally high tides above referred to come on very rare occasions, some say every twenty or thirty years. One such visited the district in January last, when Mr. Robert Thomson’s boat, “Susan,” was carried a considerable distance into the fields of the North Glen farm, and of course had to be launched from there. A peculiarity of these tides is that they ebb and flow two or three times in the one tide.

Opposite the Black Stane where the “Cordelia” came to her end lies another wreck, or rather the remains of a small vessel that was left there by its owners and became a wreck. She was called the “Rambler,” and was at one time a fine yacht belonging to the late Mr. Mackie of Balcary. Thereafter she was fitted up as a trawler, but only made one trip, it is said. Visitors fresh to the place like to get what information they can regarding these old hulks.

In the course of this story I have called up from the vasty deep memories of a goodly number of vessels and their skippers. I have tried to show what a hard life these hardy old sons of the seas had to live in order to earn a living for themselves and their families, with what courage they faced their responsibilities, and how worthy they were of our respect and admiration. Many of them found their last resting place in the bosom of the deep.

Part 13.

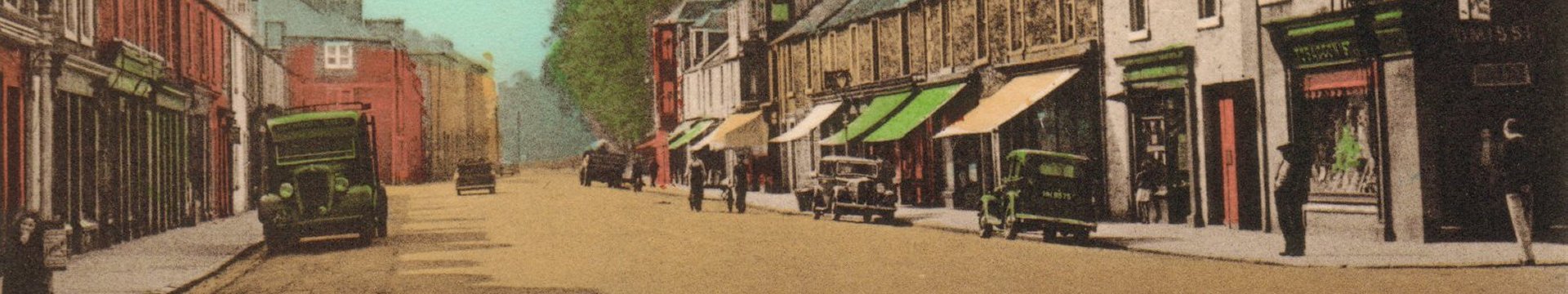

When the Scaur was the great ship-repairing centre of the South of Scotland, many vessels came from neighbouring ports to take advantage of the fine slip belonging to the Messrs Cumming. By means of the slip extensive repairs could be carried on without interference by the tide. Many of these vessels occasionally traded between the Water of Urr and Liverpool and thus became known to us all. The Kirkcudbright Fleet was perhaps the most numerous, and the vessels of that port best remembered were the schooners “Venus,” “Daisy,” “Countess of Selkirk,” “Janet Hunter,” “Jane,” “Alma,” the ketch “Marten,” and the sloops “Upton” and “Lady Maxwell.”

I have happy memories of the “Venus” when she was on the slip for a thorough overhaul some 35 years ago. It was during the summer holiday, and Captain Stitt, who was at that time the skipper and owner of the vessel, had some of his family with him. Then began a friendship that has never been broken. The “Venus” was a trim, well built schooner of 135 tons built at Preston, with fine lines, and was always a welcome visitor to the Water. In the words of “Old Schoolboy” who very kindly supplied me with some particulars of the Kirkcudbright vessels, the “Venus” finished her career ingloriously as a coal barge. The sticks (masts) were taken out of her, and she used to be towed across the Solway between Carsethorn and Cumberland. Captain Stitt skippered in turn the “Daisy,” “Countess of Selkirk,” “Janet Hunter,” “Venus,” “Utopia,” and “Marten,” until he eventually retired to a less strenuous shore life. He did many fine sailing feats in his time. He had a happy knack of knowing how to set about salving stranded vessels.

The “Utopia”

“The thing I remember most about him, however, is in connection with the wreck of the “Madras” some forty years ago. This barque of about 900 tons with a cargo of pitch pine logs whilst sheltering in the Manxman’s Lake was driven on the bar and became a total wreck. For some reason or other the lifeboat could not answer the distress signals forthwith, so Captain Stitt and Mr. Matthew Parkhill, pilot and fisherman, set off in an ordinary fishing boat and rescued the entire crew. For weeks after that, the salving of that cargo provided remunerative work for the fishermen of Kirkcudbright. The logs were gathered together and towed in rafts up to the harbour. Later on they were shipped away in old fashioned timber brigs with the big square ports in the bow through which the timber used to be loaded into the holds much to the wonder of the small boys of whom I was one.”

When the “Utopia” was running up the Dee on one voyage from Dalbeattie to the Mersey windbound she struck a mudbank, filled and sank into the sand. He got her discharged and she floated again. She was afterwards sold to the Liverpool Lighterage Company to be used as a lighter.

Many of my readers, like myself, will remember a one-armed sailor named Davy Gordon, who sailed for many years as cook with Captain Stitt. He did wonders with his one arm. When peeling the potatoes he put the potato between his knees and peeled away. He did all his own washing and kept himself very clean. He became a pensioner of Captain Stitt and got a little room to live in free of charge. On one occasion he fell downstairs and told his mother it was caused by weakness. The same weakness caused his death when he full downstairs a second time.

Messrs J. & T. Williamson, Kirkcudbright, whose firm has been mentioned as owners of several coasting vessels did a lot of trade round the coast to Rascarrel Burn, Abbey Burn, Mullock Bay, Johnny M’Dowall’s Bay, Brighouse Bay, Kirkandrew’s Bay, Ross and Rabbit Bay. “There was some excitement at times in this bay,” a well-known skipper tells me. He says “Many times I have had to take my belongings out of the vessel and wait on the beach till next tide for fear of her falling mouth down on the rocks she would be lying on.”

The “Countess of Selkirk” built at Garlieston was another fine model of a schooner owned by Messrs J. & T. Williamson. She came into the Water of Urr occasionally and was a regular trader between the Scotch and English sides. “After many adventures,” again quoting my friend “Old Schoolboy,” “she came to an end on the rocks of Ross Bay on the estuary of the Dee. Captain Thomas Connolly was her skipper for some time, and it is supposed he was lost at sea during the War. He was a daring sailor and like others of his class, did some ‘deeds of derring do.’ On one occasion he had loaded a cargo of lime on the English side and had been weather bound for some time. A shift of wind came and his crew was ashore, and could not be found, so he started off to sail her across single-handed. Half way over he was caught in half a gale. He, however, made the Ross Roads safely, but when just inside a heavy sea struck him, and the tiller broke like a pipe-stem in his hands. The “Countess” was driven on to the rocks, and the cargo, of course, went on fire. Of the fine stout little schooner only the charred ribs remained.”

The “Janet Hunter” grounded in the Manxman’s Lake, and sprang a leak. Being laden with lime she also was burned to the water’s edge. The “Upton” was a smack owned and sailed by Captain James Hughan as a coal trader between Cumberland and Kirkcudbright. She was lost on Abbey Head. Then Captain Hughan bought the “Daisy,” a fine little schooner of 65 tons built in Whitehaven. She ended her days in Laxey Harbour, Isle of Man. The schooner “Alma” traded chiefly between Cumberland and Kirkcudbright and was owned by Captain David Conning who sold her to Captain John Nelson of Gatehouse. She left Maryport with coals for Gatehouse but a strong easterly wind drove her into Garlieston Bay at low water and she grounded, which was the last of her. The “Alma” had a great history and was said to have run the blockade during the American Civil War before being sold into Kirkcudbright.

The “Lady Maxwell” was owned by Captain John Macmillan and sailed by his son of the same name. She traded between Cumberland and Kirkcudbright. She sailed from Maryport to Kirkcudbright with coals but was never heard of – another of these mysterious tales of the sea. The “Albion,” a general trader, was sailed by Captain William Macmillan and lost at the mouth of the Fleet. Then Captain Macmillan bought the ketch “Gateforth” in which he went for a cargo of slates to Beaumaris, whence he sailed for the Solway, but neither vessel nor crew was ever heard of again. The “Jane and Margaret,” a smack, was owned by Miss Stitt, the present Mrs. Treché, and commanded by Captain Peter O’Neill. She ended her days as a lighter in the Nith. Then Mrs. Treché bought the “Importer” for the coal trade. When lying at Kirkandrew’s Bay laden with coals a heavy gale from the Sou’-West sprang up and blew her right up into a potato garden where she ended her days.

The ketch “Windward” was owned by Mr. Roger Walker. She was commanded by Captain M’Dowall, who died in her cabin.

Then we had frequent visits from the Dumfries Fleet, two of which I remember well, the “Ocean Gem” and the “General Havelock.” The “Ocean Gem” was a bonnie wee schooner and for many years was under the command of Captain Richardson, of Dumfries. It would be interesting to know how many voyages this fine little vessel made between the Nith and the Mersey. During the half-century I lived in Liverpool the landing stage, one of the wonders of the world, was my favourite resort, and as the Scottish schooners were generally loading or discharging in the adjoining docks, I seldom failed to pay them a visit. Amongst them all the “Ocean Gem” seemed to be the most frequent visitor, and the most regular in her trips to the Mersey. Once when returning from North Wales in that fine pleasure steamer “La Marguerite,” we passed within hailing distance of the little “Ocean Gem” with Captain Richardson at the helm, calmly and peacefully making her way to Liverpool under full sail in a light breeze. It did one good to see a “kenn’d face” in the middle of the Irish Sea. That is the clannish spirit that seems peculiar to the Scot when away from his native land, and that makes for the success of the London and other Galloway Associations. Captain Richardson retired from the sea a few years ago.

The “General Havelock” took a new lease of life two or three years ago when a motor engine was installed in her, and she trades very regularly between the Nith and the English coast. Her skipper is Captain Alec Stitt of Barbarroch, son of the Captain Stitt above referred to, and one of the smartest seamen that ever trod the deck.

Part 14.

No story of the Kirkcudbright vessels would be complete without a reference to that fine old steam-packet – the “Countess of Galloway,” that traded between the Mersey and the South of Scotland for several generations. Every now and then her name comes up either in the Liverpool Press or the K.A. and very pleasant have been these reminiscences of her wonderful career. I think I see her yet, lying at the quay in Kirkcudbright or in the Trafalgar Basin in Liverpool where the dock wall had to be indented so as to allow room for her fine figurehead and sloping bow, and that she might lie alongside the shed allotted to her. She may be said to have been one of the last of the old paddle steamers.

My first memory of her was on one fine afternoon in May, 1859, when as a boy I was on my way to Liverpool. We left the County Town about 6 o’clock on a flowing tide and steamed down the narrow winding channel of the Dee. At times it seemed as if she would run on the rocks but the pilot knew his business and after he had safely navigated her to the estuary of the river, we dropped him and soon rounded the Ross to enter the Irish Sea. The water was calm and the passengers soon settled down to enjoy themselves, some indulging in good old Scottish reels. It must have been about 2.a.m. when the revolving Rock-Light was pointed out to me. In an hour or two we were sailing up the Mersey past what seemed to me to be a great forest of the early dawn, but which were really the masts of hundreds of sailing ships that in those days filled the Liverpool docks. The passengers were landed on the river quay, the tide not having flowed long enough for the dock gates to be opened so that the “Countess” could get to her berth.

On several occasions in after years I travelled to and fro in the “Countess” preferring the trip by sea to the long seat in a railway train. The fare was also much cheaper – a paltry 7s 6d being the cost of the return ticket in the steerage. Only once was the weather unfavourable, and as the other passengers were hors de combat with sea-sickness, I took advantage of the cook’s warm galley whilst that official was down below, and wiled away the night singing to myself some Scottish songs. – one of which I thought quite apropos:-

“Oh, why I left my hame”

Why did I cross the deep?

Oh, why left I the land

Where my fore-fathers sleep?

I sigh for Scotia’s shore

And gaze across the sea

But I canna get a blink

O’ my ain countrie.”

A lovely bright mid-summer morning followed the night of rain and wind, and when dawn came we were off Garlieston, where we landed some passengers on a boat that came for them. Then we steamed slowly along the coast passing Ravenshall and Dick Hatteraick’s Cave whilst we watched the morning mists being dispelled by the rising sun. Soon we passed the Ross and entered the bonnie river to sail up which on such a morning has always been one of the pleasantest memories of the past. The old “Countess” has a great history and a grand reputation. Her commanders whom I remember were Captain Broadfoot and Captain Milligan. I think Captain M’Queen was also her commander for some time. These men were all fine old types of coasting skippers. They took the “Countess” on her advertised trips when others dared not risk the voyage. On one stormy passage the crew of the “Countess” were able to save the lives of a ship’s crew that were in great danger.

The “Tusker” was another steamer that often called at Kirkcudbright and indeed took the sailings of the “Countess of Galloway” when the latter vessel was undergoing repairs.

There was a Gatehouse schooner, the “Resolution,” that came to the Scaur in recent years in an apparently hopeless condition. She seemed to be parting in twain at the bow, and the wonder was that she kept afloat on her passage round from Gatehouse in that condition. After some weeks of patient persevering labour she was patched up, but even then a local captain said she would founder in the least gale of wind. This was what actually happened. After a few voyages she sank like a stone not far from the Ross Island at the mouth of the Dee. Luckily the crew escaped with their lives in the vessel’s boat including the Welsh skipper who had bought her for £100 as she lay at Gatehouse and actually refused £800 for her after she had been repaired at the Scaur.

It is very possible there have been errors and omissions noticed in the course of this story. If so I shall be glad to be told of them. I am informed that the schooner “Dolphin” was sold into the South of England to carry coals between Southampton and France. The friend who gave me the information that she was sold into the Orkneys as stated in an earlier part of this story must, himself, have been misinformed. Such little mistakes will occur.

When I wrote about the ship-building industry at the Scaur, it may be that I should have mentioned the name of some of these fine workmen whose services were in great demand not only along the whole South of Scotland but in the ship-building yards of the Ayrshire coast, and on the banks of the Mersey. Outstanding amongst these carpenters was the late Mr. John Wilson, who was connected with the ship-building firm of Messrs Cumming, and who on the occasion of launches had a responsible position allotted to him. I think I see him yet making a final survey of everything connected with the ship, and looking that every cog had been lifted by the men told off to do this job, ere the final blow should be given by which the vessel was released. Mr Wilson in his early days sailed many voyages in the “Marco Polo” and brought home with him a wide experience of men and things. In the garden of his house at the Scaur were two sun-dials made by him and put into position – a lasting memorial of his more than ordinary ability and versatility. To have known such a man, and to have been able to look upon him as a friend until he ‘crossed the bar’ was a privilege I greatly esteemed for over half a century.

Visitors to the Scaur, especially those from England, are deeply interested when they get into conversation with the two or three living representatives of the former industry of the place. They are astonished to find that these village carpenters have sailed the world over in their earlier days after they had completed their apprenticeship at the Scaur. In those days, every large sailing ship carried a carpenter as one of the crew and in this way these young men gained experience. To listen to some of their adventures is a very pleasant way of spending an hour. And to hear the villagers speak of their wonderful ability in being able to tackle all kinds of odd-jobs about the place outside the repair of boats or vessels is to enlighten one’s mind very considerably. I am afraid to ruminate on the future of the Scaur when these worthy men will be gathered unto their fathers. There are none rising to take their place.

Part 15. (Story of a picnic on Heston – not transcribed.)

Part 16.

In the course of this story I hinted that there might possibly be errors and omissions, and I respectfully asked that if any such were noticed I would be glad to have my attention called to them The greater part of what I have written was derived from my own personal experience, but in the nature of things I had to get information from different quarters from those most intimately concerned in regard to certain detail, especially those connected with the Kirkcudbright vessels.

It seems that two names were omitted from the crew of the boat that went to the wreck of the “Madras” as described in Article 13. A reader very courteously puts the matter right in the following sentence:- “The party who left the beach in a fishing boat to the rescue of the crew of the “Madras” were Matthew Parkhill, Thomas Beattie, and Adam Leckie. Captain Stitt joined them on the way. Adam Leckie is the only member of the party surviving and has seen the error.”

Through the kindly interest of two or three friends I am now able to supply information hitherto omitted from the story regarding a few Water of Urr skippers. And first I am pleased to be able to give the following interesting particulars about three sons of the late Captain John Murdoch of Dalbeattie incidentally mentioned in the eighth article. The eldest son, Captain John Murdoch served his apprenticeship in the firm of Messrs J. & J. Rae, Liverpool, and was for some time first officer of the four-masted ship, the “Rowena,” trading between London and India. He afterwards took charge of the barque “Craignair,” which at that time belonged to Messrs Rae. Later this vessel was sold to a New York firm, viz., the Standard Oil Co. The firm refitted the vessel throughout in order that Captain Murdoch might take his wife with him. The latter was a Palnackie young lady, Jane Caird, who went out to New York to be married. The marriage was a very happy one, husband and wife sailing together until Mrs. Murdoch was able to take the bearings of the vessel as accurately as her husband. But fate had decreed that these two young lives were to be nipped in the bud. About 22 years ago the vessel set out from New Caledonia with a cargo of chrome ore for Philadelphia and New York but she never reached her destination. It is presumed she went down with all hands – Captain Murdoch and his wife and seventeen of a crew. His father was always under the impression that the cargo had shifted.

A younger brother, Captain James Murdoch, sailed for many years as master of the schooner “Isabella,” trading between Dalbeattie and Liverpool. This vessel was afterwards sold to an Irish firm and under the new ownership was lost on her first voyage. Captain James then had charge of the brigantine “Mayfield,” of which vessel he and his father were part owners. She was engaged in the continental trade. Captain James was a very industrious skipper and contrived to get out of port when others deemed it advisable to stay at home. He was in fact a born sailor. Following his usual “go-ahead” policy he bought a three-masted schooner, the “Red Rose,” and sailed with her for several years in the same trade. We next find him in command of another vessel, the barquentine “Raymond,” which he had also bought for the continental trade. In the meantime the “Red Rose,” under the command of another master, was run down and sunk in the Straits of Dover, the crew fortunately being saved. Captain James sailed the “Raymond” between this country and the continent during the whole of the blockade. On one occasion the vessel was attacked by a German submarine which fired four shots into her. Captain Murdoch and the crew were ordered to take to the boats, but feeling rather reluctant to do so they purposely delayed the operation. “Take to the boats you English swine,” came the chorus from the submarine. The Captain relied. “We’re not English, we’re Scotch.” “That’s a d— sight worse” came the answer as another shot was fired into the “Raymond.” Luckily at that moment a French destroyer hove into sight and the submarine quickly submerged. Two or three shots were fired but the destroyer failed to find its mark. Considerable damage was done to the “Raymond” but fortunately none of the crew was injured. The “Raymond” was escorted into Brest by the destroyer and had all the necessary repairs effected. Captain Murdoch was afterwards complimented by the Admiralty for his action, and was compensated for the damage done to the vessel.

Captain Alex Murdoch, the youngest son, sailed with his father for some time in the schooner “Resolution.” He afterwards joined the barque “Chipperkyle” belonging to Messrs J. & J. Rae, Liverpool, trading between the latter city and Australia. On the first voyage after he left her she was lost with all hands. He was appointed second officer on the barque “Bengairn,” also belonging to Messrs Rae, and with her took the first cargo of nitrate to be delivered at Yarraville, Melbourne. Leaving her, he afterwards joined the minesweeping branch of H.M. service and was placed in charge of various vessels of this type materially assisting to clear the mines from the North Sea. Strange to say, the “Bengairn” also met a tragic fate, being torpedoed by the Germans on her homeward voyage from San Francisco with a cargo of grain.

Captain Robert Bie, belonging to a well-known Co’en family, began his seagoing career on board his father’s vessel, the “William Thomson,” but afterwards joined the Blue Funnel steamers, and was in command of the “Alienous” at the time of his death. It was a remarkable coincidence that he was born at Rockcliffe, Colvend, and was buried at Rockcliffe, America.

I am grateful to be able to pay a tribute to a brave Dalbeattie sailor, Captain Samuel Markham. During the late war, after getting his certificate as master, he was chief officer on the “Bellarado” when that steamer was attacked off Malta by an Austrian submarine. The officers and crew gallantly defended themselves and the vessel sinking the submarine with their last shot, but at a heavy cost as both the chief officer and the captain were killed on the bridge. Captain Markham was buried in the naval cemetery at Malta with naval honours.

A much respected and well-known Colvend resident during the last few decades was Captain Major who passed away at Rockcliffe last year. During the earlier days of the Scaur regatta he acted as commodore with much acceptance. One incident of his life has come to my knowledge and is worthy of record. On one voyage his Chinese passengers mutinied, and Captain Major was the only one left to navigate the ship. Instead of steering the course set by the mutineers, with the aid of a magnet he steered the vessel in the direction of a British man-of-war, under whose guns the mutineers found themselves one fine morning much to their surprise and undoing.

The many friends of Captain Robert Edgar, Kippford, will be pleased to hear that one of his sons, Captain Thomas Edgar, has been promoted to the command of the steamship “Tintorado,” belonging to the Lamport and Holt Line, and sailed last week for Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, and Santos in Brazils. He is the youngest captain in the employ, being only 31 years of age.

And now a closing reference to an old school companion at Barbarroch school when we were boys together. I refer to Captain Matthew M’Lellan. After sailing the seven seas he retired to spent the evening of his life in his native village of Barbarroch. At one time he was commander of the well known sailing ship “Annie Fletcher,” but afterwards went into steam, and for a number of years sailed from the Clyde. To meet these friends of our youthful days after a lapse of over sixty years, and to recall happy memories of the old school that stands at the corner of the Colvend and Kippford roads is a pleasure and a privilege that are granted only to a very few.